What’s the angle?

Somewhere in the migration of kayaking from the Arctic to Europe there was a major change in paddles. Arctic paddles all had long narrow blades, with both blades in the same plane. Apparently based on rowing oars, the paddles used in the Rob Roys and other kayaks used short, wide blades.

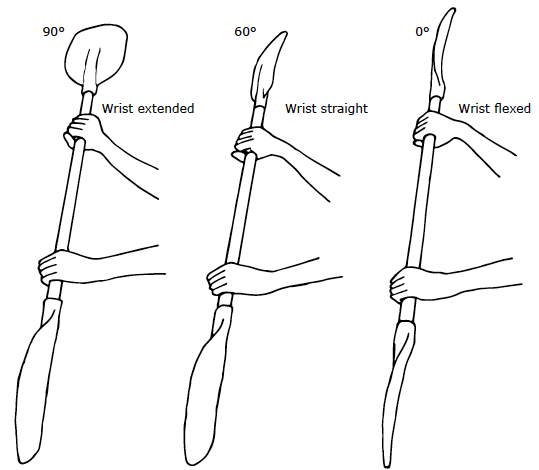

Someone realised that when paddling into wind there was a lot of wasted energy pushing the top blade through the air. The solution was to have the blades ‘feathered’, 90° from each other. By controlling the paddle with one hand firmly gripping the paddle with the other allowing the shaft to rotate, both blades could be placed in the water at the correct angle. With the control-hand blade in the water, the wrist was straight, with the other blade in the water, the wrist of the now pushing hand was extended 90°.

But that led to a problem, besides the obvious one of confusing beginners: overuse injuries in the controlling hand, extended and straightened at each stroke. Another problem can become apparent in gusty crosswinds. Yet the 90° feather remained the standard for many years, in both competition and recreation.

There were those who maintained that feathered paddles were bad, and always used unfeathered paddles. Some still do. But that can lead to other problems.

So who is right, or is there some middle way? It depends... In the diagram, the right hand is the controlling hand and the left blade is in the water.

The Arctic hunters generally paddled with low strokes, not lifting their blades high in the air. There was little or no extension or flexion in their wrists, so no tenosynovitis and their blades were at the correct angle in the water. Modern unfeathered paddles also work well enough with low strokes, like sweep strokes.

Watch a Sprint paddler and you’ll see the top hand at about eye height at each stroke, the blade well above the head. Very different from the Arctic style, and if you try it with an unfeathered paddle you’ll be back with the headwind problem, and will now either have to flex the wrist of the controlling hand, or switch control hand at each stroke.

Flexing the wrist means we’re back to wrist problems. Switching the control hand, i.e. right hand controlling with right blade in the water and vice versa, may lead to irregularities at high cadence or in turbulent waters.

Hold a paddle as you normally would when paddling. Now, without extending or flexing your wrist, lift your controlling hand as if to make a stroke. What’s happened to the angle of the other blade? Just lifting the hand has rotated the shaft, and if you get the angles right you can paddle without straining your wrists.

What is the angle? Not 90°, not 0°, but something in between, depending on the length of the paddle and your paddling style. To find the angle, assemble a two-part paddle with zero feather and leave the joint unlocked. Grip with both hands and set up to make a stroke on the non-control side. The blades will now be feathered at the correct angle. Lock the joint and try paddling.

The usual range is between 60° and 30°, higher paddling styles using angles nearer 60°, lower styles nearer 30°. The answer might even be 42.

Experiment until you have the angle that suits your paddle and style. And if you paddle different boats with different paddles you may find the angles will be different too.

Carpal tunnel syndrome should need no longer be of concern to paddlers.