One Summer’s Paddling: Crossing

Port Lincoln to Adelaide, 23 January–2 February

Joining us was Ray Rowe1, an instructor at Plas y Brenin, the British National Centre for Mountain Activity, one of the most experienced British sea paddlers and on a working holiday in Australia. Ray travelled to Port Lincoln by road with friends but John and I went by Troubridge. At three in the morning we were woken by the captain so that we could see something of the coast we were to pass later. Interesting by moonlight, but our view was to be very different.

The policeman who accepted our TP 168 forms2 this time sounded almost indifferent. Next morning, January 23, with the local media watching, we set off across Boston Bay and then turned south to Thistle Island. We stopped for lunch at Observatory Point and moved on.

[Picture: John nearer camera]

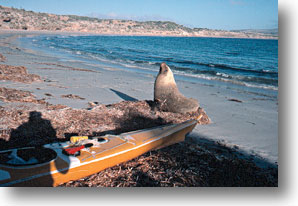

Thistle Island is a sheep property and tourist resort. Our brief visit to the house to report our arrival was rewarding as we were given freshly caught and filleted fish for tea and advice about the effects of UV on the eyes from a visiting optometrist. We spent the night in a sheltered spot at the southern end of the island. In the morning we found our site had been given the seal of approval by another visitor, who woke and held his nose in the air in classic pose before lurching back into the sea.

Wedge Island, 15 nautical miles away, was our next goal. This was to be no coast hugging trip but an open crossing, and we had to be satisfied with weather and sea. Conditions at the surface were good, despite some rapidly moving clouds above, and we set out. Open crossings can be very tedious, with the land ahead seeming to come no closer and the land behind not appearing to recede. Nothing appears to change. On this occasion petrels and dolphins made paddling across smooth swells more interesting, and after 4 3/4 hours we were on shore again.

Wedge Island is also a tourist resort, with most visitors flying in, and more people learned something about sea kayak expeditions at our camp in the middle of the long sandy beach on the north coast. The south coast is sheer cliff, and gives the island its wedge shape.

Conditions for the next crossing, to the foot of Yorke Peninsula, were near perfect. Since we could not see the land ahead we paddled by compass. [In the picture: Looking back, Ray nearer camera] Ray and I had compasses and we took turns of 15 minutes, as paddling by compass is a wearisome task, with no external directional reference. Without accurate information on tidal streams we found ourselves making landfall at West Cape, a little to the south of our aiming point. We lunched and then followed the coast, rugged limestone cliffs, past the wreck of the Ethel3 to Stenhouse Bay and debated whether to stay or move on in the dark. We stayed.

A change was forecast for the next day. With the wind changing periodically, rain at one stage, and many cloud changes, we paddled along a rather flat, uninteresting coastllne. By late afternoon the real change could be seen approaching so we landed at a place called Point Gilbert.

[Picture: Early morning out of Stenhouse Bay4, Ray in centre]

Now the weather struck. In miserable conditions of strong gusting winds and driving rain we pitched the tents and cooked tea. When it eventually eased a little I moved up to the shelter of bushes in the sandhills to avoid the worst of the wind, while John and Ray spent the night bailing a leaking tent. It was pitched crosswind, allowing rain to be driven up under the fly.

Lying around5, sleeping, and listening to reports of a boat abandoned off the north coast of Kangaroo Island and floods in the north of the state was all we did the next day. After two more days of Strong Wind Warnings we decided that we had seen more than enough of Point Gilbert and moved on despite the weather. In any case, we wanted to be at Edithburgh to be able to take advantage of the next calm day.

The headwinds, with their chop, became cross winds and then following wlnd and seas as we made our way laboriously past the new Troubridge lighthouse [in picture] and into Edithburgh where we were generously offered a caravan and great hospitality.

A somewhat annoyed policeman sought us out, asking where we had been, why we hadn’t made contact, and claiming that Marine Operations Centre Canberra6 and emergency services had heard nothing of us for a week. We explained that we had no ready communication but relied on sending messages by others, as we had done at Thistle and Wedge Islands and Stenhouse Bay, although the last had clearly become garbled. There had been no telephone and noone at Point Gilbert, but we were carrying flares and a VSB7, and if we had needed assistance we, and not others, would have called. In any case, we had been readily visible on the beach at Point Gilbert to anyone who had really wanted to find us.

He was eventually satisfied, and when I later wrote to MOC learned that there had been no real panic for us. The point must be made, however, that any expeditions like ours must have all the required equipment and a responsible agent, Ray’s wife in our case, to handle all communication with emergency services, the media, etc., and it must be the group’s own responsibility to either solve their problems on the spot or if that is not possible, call for assistance. That responsibility cannot be taken by people elsewhere who do not know the real situation.

Two more days of Strong Wind Warnings followed and we gazed across the gulf, unable to see the Adelaide Hills on the other side. We did learn something of Edithburgh and its interesting early history.

It was 03:40 on February 2 when we launched again. We paddled out in the dark, the only lights our shielded Cyalume® compass lights, the stars, and phosphorescent plankton sparkling in the bow waves and paddle vortices. A fascinating experience, but one demanding concentration, both when leading the group on compass and also when following in formation.

A faint orange sliver of moon rose later, to be followed by Venus, and then the dazzling Sun into a near cloudless sky.

As we pressed on, stopping every hour for something to eat and drink, or to pump the cockpit dry, the light easterly breeze faded to glassy calm in the centre of the gulf, and then changed to a light southerly as we approached our landfall. We were heading for Glenelg and were able to resolve its buildings a couple of hours out and head towards them.

At a few minutes past three we were on shore again. Thirty eight nautical miles ln 11 1/2 hours, the longest crossing ever made in South Australia by kayak. It was 40° C on shore and we were glad to see the journalists go, allowing us to pack things away and go home to a cool spot.

We were gratified by the generosity and hospitality we had received, and heartily thank the companies and individuals who gave or lent us materials and equipment, the fishermen who reported our progress, and the many helpful people we met along the way.

A summer to be remembered.

Notes

1 Ray later worked for the British Canoe Union, his role including editing the BCU Handbook.

2 Form TP 168 is the small ships movement reporting form. I listed engine type as ‘Homo sapiens’ and fuel as ‘adenosine triphosphate’.

3 The remains of the Ethel have now broken up, and there is little to be seen.

4 The monochrome version of this photograph was used, laterally inverted, by a UK company, Decal Designs, as the basis for a sticker. When I discovered and queried this I learned that the editor of Canoeing was connected to the firm. I requested, and received, a number of stickers. This slightly scuffed one is on my Nordkapp.

5 During this time I devised the idea of attaching a length of shaft with a T grip to one half of a split paddle to make a usable single blade paddle for emergency use. I used the idea for a time, then took to carrying a specially made single blade paddle, using whichever paddle was appropriate at the time, as did some of the Arctic peoples. Others have since taken up the idea.

6 MOC is now the AusSSAR Rescue Coordination Centre, an agency of the Aus Maritime Safety Authority.

7 VSB: VHF Survival Beacon, what is now known as EPIRB, Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon. In this case it was a military 243 MHz beacon that John had borrowed from a friend in the RAAF. We debated whether or not we should take it, and eventually John carried it, probably because it was the easiest way to take it home.